Disproportion about proportion

In my review of Adam Wagner’s Emergency State I talked about proportionality:

Proportionality is a key concept in human rights law, and Wagner’s approach and my criticism of it may be explained by different instinctive approaches to proportionality. … Perhaps my background as a former government lawyer makes me tend to allow a substantial margin for a range of different policy approaches all to be justifiable, whereas some very human rights-minded lawyers can seem to think proportionality is a search for the one and only exquisitely calibrated ideal response, with all “really existing” options presumptively unjustified. I see this approach as hypercritical, and making it difficult to recognise, acknowledge or support proportionate measures when you see them.

There was an interesting judicial review judgment the other day, against the anti-lockdown protester Deborah Hicks (it was one of two cases she lost, in fact), who’d claimed that a Magistrate’s Court, having convicted her of breaching coronavirus lockdown regulations in 2020, had unlawfully refused her permission to appeal on a point of law to the High Court (something that’s called a “case stated appeal” because in legal jargon the Magistrates’ Court “states a case” to the High Court; I’ve never known why this particular procedure has this name, but it’s a very interesting, highly legally technical sort of criminal appeal).

Mr Justice Chamberlain explains the facts (para 3 of the judgment):

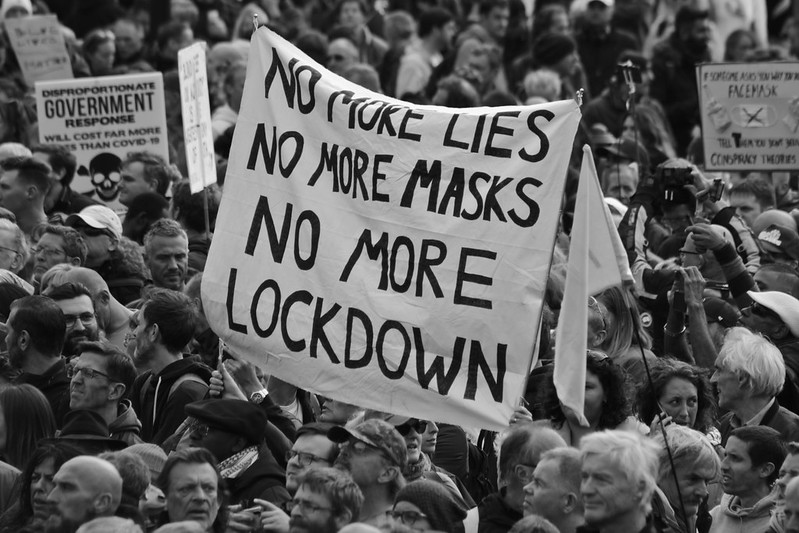

On 16 May 2020, there was a protest in Hyde Park against the lockdown. Debbie Hicks learned of the protest and decided to attend. She drove from Stroud to London and then took the underground to Hyde Park, arriving at about 12.30pm. At 1.10pm, Ms Hicks was standing on the edge of the crowd, which numbered over 100. Police Constable Casey of the Metropolitan Police approached her, explained that she was committing an offence under the Regulations and directed her to go home. She responded that she did not care and attempted to argue with the officer. PC Casey explained that failure to comply could lead to a £60 fine. She did not leave, so PC Casey issued an FPN for £60. She did not pay and was charged with contravening reg. 7 of the Regulations.

Regulation 7 made it unlawful to take part in a gathering of more than two people in a public place.

If you’re interested in the law of the pandemic and the law of protest, as I am, you’ll be interested in the whole story, and in Chamberlain J’s rejection of Ms Hick’s complaints. But I want to make a particular point about proportionality.

Deborah Hicks asked the judge to state 7 questions to the High Court, which you can read at paragraph 7 of the judgment. In those draft question she raises questions of proportionality repeatedly, wanting the Hight Court to consider:

Did District Judge Snow carry out a correct analysis of proportionality of interference with human rights … Did he fail to assess the proportionality of the interference with human rights posed by the regulations, as opposed to only considering the proportionality of the court finding her guilty of the offence? … Did he fail to properly consider proportionality of the interference with Ms Hicks’ human rights at all? … Can it be said that the interference by the Government with human rights … by restricting gathering to protest during periods of national lockdown was proportionate given that there were less restrictive measures available …

Chamberlain J unsurprisingly saw no problem with the proportionality of the conviction.

Think about this way. She drives a long way to this unlawful (and perhaps in some people’s view dangerous) protest, then takes part in it for 40 minutes without a legal problem. Even when a police officer approaches her, all that happens is she’s told to go home. Then even when she refuses to comply, all that happens is that, in effect, she’s fined £30 (which is all she would actually have paid had she just got her debit card out within two weeks). Deborah Hicks decides to fight that all the way to the High Court.

Who’s been disproportionate here?